Field Trip led by Joan Lentz, Tim Matthews, Larry Ballard and Susie Bartz.

Reported by Laura Baldwin, photos by John Evarts.

In June, about 24 Society members enjoyed a stunning 24 hours atop the region’s highest mountain (8847 ft.) with some of our area’s best teachers and naturalists. We found tectonic plates crashing together downslope; ancient alpine mat-plants hunkered down for the centuries, their tiny flowers attended by tiny butterflies; and a good variety of montane birds foraging, parenting, and vocalizing.

In June, about 24 Society members enjoyed a stunning 24 hours atop the region’s highest mountain (8847 ft.) with some of our area’s best teachers and naturalists. We found tectonic plates crashing together downslope; ancient alpine mat-plants hunkered down for the centuries, their tiny flowers attended by tiny butterflies; and a good variety of montane birds foraging, parenting, and vocalizing.

Some participants arrived at Mt. Pinos Campground on Friday afternoon, under a sky filled with towering storm clouds. Thunder rumbled, rain showers fell, Joan Lentz and Tim Matthews welcomed it all. We followed Pygmy Nuthatches to their nest holes in old stumps and watched them feed their young. White-headed Woodpeckers drilled into pine trunks. Cassin’s Finches bathed in a rare rain puddle. Fifteen bird species were seen before dark.

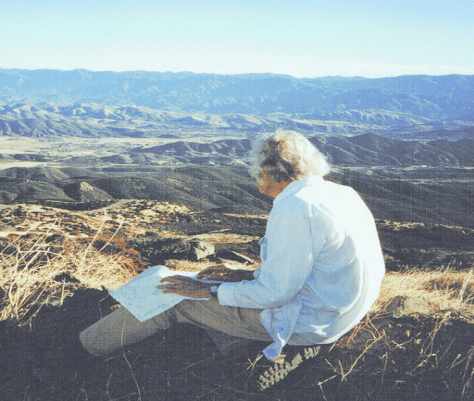

We were wonderfully fortunate to have Joan Lentz, author of A Naturalist’s Guide to the Santa Barbara Region, co-lead this trip. Her book is a peerless resource, highly recommended for its readability and thorough coverage of a vast subject. This trip culminated a series of SYVNHS field trips to local habitats described in A Naturalist’s Guide. Lentz graced the evening campfire with stories of a lifetime’s adventures in these mountains with mentors and colleagues, beginning with her grandfather Robert E. Easton and father Robert Olney Easton. After dinner she led us on a starlit walk among tall pines, searching for owls.

Next morning we gathered at Iris Meadow, at the end of the paved road. A walk around the meadow yielded 18 bird species. Birds gathered fruit from Wax Currant bushes, hawked insects above the massed Irises, and fed their young in cavity nests high in Jeffrey Pine trees.

Susie Bartz unveiled a panoramic geologic map of the region and its faults. There are four: the Garlock, Big Pine, San Gabriel and San Andreas faults all come together near the northern base of Mt. Pinos where the San Andreas makes the Big Bend, indicating tectonic plates shifting, grinding, breaking and uplifting Mt. Pinos, Mt. Frazier and Mt. San Emigdio.

Susie Bartz unveiled a panoramic geologic map of the region and its faults. There are four: the Garlock, Big Pine, San Gabriel and San Andreas faults all come together near the northern base of Mt. Pinos where the San Andreas makes the Big Bend, indicating tectonic plates shifting, grinding, breaking and uplifting Mt. Pinos, Mt. Frazier and Mt. San Emigdio.

The hike to the summit of Pinos is short in distance – two miles – but rich geologically and biologically. Larry Ballard explained the rare alpine fell-field and the flora that has evolved adaptations to cope with the brutal conditions – a short growing season, thin soil, extreme temperatures, and prolonged summer drought.  Because Mt. Pinos sits at the confluence of the Transverse Ranges, the Coast Ranges, the Central Valley and the Mojave Desert, the unique flora reflects influences from each. Many plants are low, slow-growing, hairy or waxy or both. They form mats; they live for decades or possibly centuries and flower briefly. Highlights included Spurry Buckwheat, Wright’s Buckwheat, Dwarf Lupine, Whitney Milk-vetch, Pine Gilia, Granite Gilia, and a tiny Blazing Star. Tim Matthews opened our eyes to the many pollinators and rare butterflies on these plants, including Duskywings, Blues and Hairstreaks. Joan Lentz pointed out Green Towhee, Red Crossbill, Clark’s Nutcracker and 17 other bird species making the most of the brief alpine summer.

Because Mt. Pinos sits at the confluence of the Transverse Ranges, the Coast Ranges, the Central Valley and the Mojave Desert, the unique flora reflects influences from each. Many plants are low, slow-growing, hairy or waxy or both. They form mats; they live for decades or possibly centuries and flower briefly. Highlights included Spurry Buckwheat, Wright’s Buckwheat, Dwarf Lupine, Whitney Milk-vetch, Pine Gilia, Granite Gilia, and a tiny Blazing Star. Tim Matthews opened our eyes to the many pollinators and rare butterflies on these plants, including Duskywings, Blues and Hairstreaks. Joan Lentz pointed out Green Towhee, Red Crossbill, Clark’s Nutcracker and 17 other bird species making the most of the brief alpine summer.

At the summit an exhibit explains something of the sacred significance of this mountain to the native Chumash people. The mountain was considered to be the center of their world; it felt that way for those on this trip too, thanks to the experts who generously revealed its riches for us.